I didn’t set out to steal a cat. Or write a story about it.

I set out to survive the kind of grief that guts you from the inside. The kind that makes you keep seeing shadows that aren’t there and crying in grocery store aisles. In the end I guess that kind of story kind sort of writes itself and then waits for you to recognize it (even if it takes six years) and sit down and get on with it.

This isn’t really a story about theft.

It’s about loss. And love. And the messy, irrational things we do to feel whole again.

It’s about Stuart, the cat who broke my heart by being the best thing in it.

And Stella, the tiny, cross-eyed stowaway who climbed into the hollow he left behind.

Most people think he was named Stu because it was short for stupid. And who knows, maybe at first it was. But for as long as I can remember, across those too-short fifteen years, it was short for Stuart James, named after James Stuart II, my favorite of all the British monarchs (of course I have a favorite monarch).

He was my best friend in more ways than I can explain.

He was weird-looking, lanky, scraggly, even at his healthiest.

He walked on his tiptoes, had a wonky eye, and scars on his nose, lip, and head.

Reminders of a life on the streets, and brushes with death that probably claimed a few of his nine lives before I claimed him as my own.

He was almost all white, except for an orange-ringed tail and a few scattered orange patches across his back and head.

And he was loyal.

He knew all my stories. I won’t pretend he didn’t judge me…he was a cat, after all, and judging is innate to his kind, regardless of his judgy nature, he loved me unconditionally. And he never told a soul the deepest, darkest secrets I whispered to him at night.

He was quirky in the way only soulmates are. He did this thing I’ve never seen another cat do. He would jump straight from the ground into my arms. Not in the slow, climbing way kittens do on Instagram reels. No. He’d pace in front of me, mewing, while I patted my chest and asked, “Wanna come up?” He’d pace some more, maybe complain a little louder, and then…leap. A full five-foot arc, right into my open arms.

I thought it was a magic trick. Sure, dogs do it. Kids do it. (even educated bees do it?) But cats? Cats don’t perform. They do what they want, when they want. For Stu, that leap was the ultimate act of trust, me, trusting he wouldn’t claw the shit out of my chest, and him, trusting I’d catch him every time.

He was also, hands down, one of the most expensive things I’ve ever owned, aside from my house and current car. I’m pretty sure his vet bills totaled more than my first car. There were at least three emergency vet visits: urinary blockages, a chewed lily leaf (how that didn’t kill him, I’ll never know), and various death-defying stunts. But every time, the vet would say, “He can make it if we treat him.” And how do you say no to that?

As much as I loved him, I’ll admit it. I get mad about it sometimes. Pets are heartbreak by design. I can’t remember which comedian said it, but the bit went something like: “Look, kids…a puppy! In fifteen years it’s going to break your heart and crush your soul.”

We don’t deserve pets.

And they don’t stay long enough.

As fate would have it, they stay just long enough to become a permanent part of your soul.

And then they die.

And you get a little box of ashes to keep in your china cabinet.

(At least that’s where I keep mine)

Maybe you get a ceramic paw print too—someone smashes their dead paw into clay before they set them on fire.

It’s absurd.

It’s tender.

It’s cruel.

I watched him grow old. In the last few months, I could see him fading. Slow down. He stopped jumping into my arms. He didn’t even pace for it anymore. He just watched me, his body still trying to obey the instincts that had always made him bold, but the strength wasn’t there. I started letting him come outside with me. He never wandered, just found a sunny patch of grass and curled into it like he was part of the earth itself. He moved slower. Slept longer. Ate less. No matter his age, he still followed me to bed. Our bed is high, raised up on a platform that takes a small leap even for a healthy cat. But somehow, every night, he made it. He’d settle between our pillows, tuck himself close, and stay there all night. In the morning, he’d stretch his paws out, touch my nose, and meet my eyes with that same quiet knowing he always had.

That was my life for fifteen years.

I don’t know how I knew, but I knew.

Some deep feeling inside me.

Maybe it was just because he looked tired.

His body was thin, almost brittle. His breathing was shallow, less… like a clock winding down. Each tick growing further apart. A countdown you can hear and feel. One you try to ignore.

His fur wasn’t matted, but it was off. Dry, unkempt. He had lost his shine.

And his eyes, they were still soulful, still saw into me, but there was something else in them now.

A pleading. A knowing.

And as I looked into his eyes, I saw it.

And I knew.

This was our last night.

He curled into the crook of my arm, like always. I cued up our playlist, The Droge & Summers Blend, a song called Two of the Lucky Ones, was on first. It was one of his favorites.

I pulled him closer to me and I started to cry.

As Peter Droge sang by the light of a setting sun I whispered “You can go now baby. Mama will be ok if you need to go. I’ll be ok, I’ll be ok, I’ll be ok…”

The next morning, we woke to find he had wet the bed between our pillows. He didn’t try to hide it. Didn’t move from it. He didn’t look ashamed, he just looked… finished. He had listened. And I had promised.

So I called our vet. I made the appointment.

When the time came, I held him through both injections.

I held him after the vet whispered, “He’s gone.”

I kept holding him while my body shook and the tears fell in heavy, soaking drops.

T stood beside me, close but not touching.

He was sobbing too.

But I think he knew, if he touched me, I would collapse.

I was tethered to this limp, lifeless body, and I wasn’t ready to let go.

T whispered, “He loved you so much.”

I cried so hard the vet tech cried too.

Even Dr. Plott cried.

I didn’t stop crying for days.

(I’m crying now as I write…and rewrite this.

I don’t cry less with each version.

I’ve come to accept this will always hurt.)

Time doesn’t heal all wounds.

That’s bullshit.

That’s what people say when they don’t know what else to say.

When you’re sobbing over a cat and your grief makes them uncomfortable.

I loved that fucking cat. And when he left, it felt like someone reached inside me and took the part I hadn’t realized was holding everything else together. My world cracked wide open. I couldn’t speak his name without breaking. I couldn’t sit in the places he used to sleep. I couldn’t bear the silence.

And then… came a text.

Two days after I held Stuart for the last time, I was still crying in waves, grief arriving in strange, sharp bursts, like my body kept remembering what my heart already knew.

The text was from a friend. No context. Just a photo of a tiny, somewhat cross-eyed Siamese kitten with huge, ridiculous blue eyes and ears too big for her head. Below it, a message:

“I know you just lost Stu… but do you want a kitten?”

I stared at the picture for a long time. I felt guilty just looking at it. Like even entertaining the thought was some kind of betrayal. I hadn’t vacuumed up his fur yet. I hadn’t showered, but I had at least washed the bedding. His dish was still in its place.

But the ache inside me was unbearable. My arms felt too empty.

So I replied: “No”.

But, I couldn’t get that picture out of my mind. That tiny kitten looking up at the camera, eyes slightly crossed, ears like satellite dishes, fur too thin to be impressive but thick enough to whisper potential. She wasn’t cute in the obvious way. She was awkward and wild-eyed. Desperate, maybe. But also… cavalier.

Like she was saying: Come get me if you want. If not? I’ll figure it out.

I stared at it again that night. And again the next morning.

I showed T the picture and said, “Can you believe Heather? We don’t want a kitten right now…”

I didn’t respond for three days.

I kept telling myself no.

No, because I wasn’t ready.

No, because she wasn’t him.

No, because I hadn’t even vacuumed. His dish was still there.

His favorite food, Mixed Grill, was still sitting on the counter.

And I still cried every time I walked into the bedroom and settled in without him.

And because I was still seeing him in the periphery, in the margins. Like a comment from an editor I wasn’t ready to read. This heavy reminder of unfinished business. Something that might one day become just a footnote, but for now it lingered and it demanded attention.

The white fake lilies Morgan bought me as a joke would catch the corner of my eye, and for a split second, that flash of white… it was him.

But the picture haunted me (as if I wasn’t haunted enough)—and gave me hope.

I’d open it and stare. Close it. Open it again.

That little punk cat wouldn’t blink.

Finally, I broke.

“Where is she?” I texted.

Heather replied immediately, like she’d been waiting for it.

“At my mom’s camp in the mountains. She just wandered up and she’s worried the stray dogs are going to kill her.”

She sent another picture. Cuter than the last.

Oh…

Well…

Shit.

Now it wasn’t just a maybe-kitten. It was a maybe-murdered kitten.

A potentially soon-to-be tragic-eyed ghost I would also carry around in my chest cavity for the next decade if I didn’t at least try.

The moral math didn’t make sense. I was grieving. I was still crying in the grocery store. I hadn’t cooked, hadn’t slept, hadn’t gone a full day without whispering “I miss you” to a patch of carpet.

But this wasn’t about being ready. It was about not being able to live with myself if I didn’t do something.

I went back to T with the new picture.

He looked at it, nodded slowly. “Yeah… it’s a kitten. And it’s cute.”

I stared at him. “Do we want a kitten?”

He didn’t hesitate. “It’s up to you, babe. I know how bad you’re still hurting.”

I rationalized. “I think Rooney’s lonely. She misses Stu… she needs a friend.”

T raised an eyebrow. “Rooney is fine.”

I wasn’t deterred. “I mean… she seems really sad, doesn’t she? Doesn’t she seem lonely? That’s depression, right?”

He didn’t answer.

So I tried again. “Do you want a kitten?”

He just repeated, soft and steady: “It’s up to you.”

Which, of course, meant: I will support whatever your broken, irrational heart decides to do—even if it means a day trip to the mountains to rescue a stray kitten that probably doesn’t need rescuing.

We thought she was a stray. Unwanted, unclaimed, a little ghost scratching out an existence around a camp in the mountains of North Carolina. Heather’s mom had found her, said the wild dogs were circling– the kitten wouldn’t last much longer. That was all we knew. That was all I needed to know.

I texted Heather, “Fine. Tell Beth we’ll take her.”

As luck would have it, Beth and Pampa were already heading to South Carolina the next day. She said she could meet us on the way down from the mountains. We picked a Chick-Fil-A in Gastonia. Neutral territory, almost halfway for both of us. Public enough to not feel like a shady animal deal, but not so busy that anyone would ask questions.

So we packed the cat carrier. Gassed up the car. Started driving.

It felt a little ridiculous, even in the moment. Like we were on some noble quest to rescue a lost soul while trying to heal mine. But I didn’t care. I needed something to pour my grief into. I needed something I could save.

T drove. It was quiet. I stared out the window, thinking about how recently I’d made this same kind of drive, but in reverse. From the vet’s office. Without Stuart. With every mile, I doubted myself. I wasn’t ready. But I was already going.

Beth met us in the parking lot, kitten in hand. She was tiny, smaller than I expected. All ears and eyes and fragile limbs, folded into Beth’s arms like a secret.

“I’m so glad you’re taking her,” she said.

I took the kitten carefully, holding her close like she might vanish if I didn’t keep her pressed to me. We made the usual small talk, said thanks, and loaded her into the carrier. I climbed into the back seat beside her. Left the carrier door open. Kept my hand inside.

On the ride home, T kept glancing back at us in the rearview mirror.

“I’ve thought of a name,” he said.

I was sort of shocked. It had taken us weeks to name Rooney. T had been calling her Dan the Adventure Cat when she was still feral in our backyard. Because, as he told me, “all outdoor stray cats are male”. I didn’t get the logic, but I didn’t deny him the fantasy. And when we realized Dan was, in fact, a she, we went through a whole series of terrible almost-names: Chicken. Danielle. Kitten Butt.

Nothing stuck.

Then one day I made the leap—from Dan to Dan Rooney. The Steelers. Pittsburgh.

I remember yelling it down the hall from the toilet:

“ROONEY! We should call her Rooney!”

And that was that. Dan the Adventure Cat, became and is still known to this day as: Dan “the Adventure Cat” Rooney.

So for T to have a name within ten minutes of picking up a kitten we were not prepared for or even sure we wanted…that was impressive.

“Stella Blue,” he said. “You know, because she has blue eyes.”

T’s a Grateful Dead fan. It made sense.

And just like that, she had a name.

Stella. Our new baby.

She didn’t hiss. Didn’t scratch. Just stared. Still wide-eyed. Still that strange blend of desperate and defiant. Like she was thinking, You got me? Fine. Just don’t fuck it up.

When we got home, I decided she needed a bath. She’d been living under a porch, allegedly. Surely she had fleas, mites, worms—something.

I started to run the water and reached to lift her, but then I noticed… she wasn’t dirty. Her coat was clean. Her ears were clear. She didn’t smell like garbage or wet leaves. She didn’t even flinch when I touched her feet.

And then I saw it.

A faint line around her neck.

A collar line.

“T,” I called. “Come here. Look at this.”

He stood beside me, and I pointed. That perfect little imprint. The one you only get from something worn too long to forget.

“This cat was wearing a collar.”

And right then it hit me. It hit us.

I said, “Oh my God.”

T said, “Beth stole this cat.”

We both said, “And we helped her.”

I made T text Heather.

“Ask her where the cat came from. Don’t let her skip the details. We know the truth”

That’s when we got the whole story.

Apparently, the kitten had wandered up to Beth’s camper and started hanging out under the porch. She’d been wearing a flea collar, one of those cheap, one-size-fits-all kinds. But it was too tight. And whoever had put it on her hadn’t bothered to cut off the excess length, so she was just dragging around six inches of loose collar behind her like a tail extension.

Beth said she was afraid it would get snagged on something and choke her.

So she cut it off.

Which is when, I suppose, she decided the kitten was now hers.

Either to keep, or to give away.

And since she opted for Doorway Number Two…

By extension…ours.

That first week, we kept Stella quarantined in our bedroom.

Just to be safe.

We didn’t want her passing anything to Rooney. We had a vet appointment scheduled, but they couldn’t see us until the following Monday.

It felt responsible, like we were pretending to be people who knew what the hell they were doing.

We’d had cats before…

Just not stolen ones.

So it also felt dangerous.

Because what if she was microchipped?

What if someone had reported her missing?

Or worse…

stolen?

What if by taking her to the vet, we were writing our own ticket to jail?

We lived mostly normal lives during this time, but occasionally one of us would muse outloud, “do they arrest people for stealing cats?”, “since we didn’t cross state lines, this isn’t a federal crime right?”, “what if her owner wants her back?”

I think that’s what scared me more than anything. Not the jail, because surely they’d throw Beth in jail, not us, I mean we were just recipients of stolen goods, not the stealers, so what, probation? Community service? I could live with that. What I couldn’t live with though was giving her back. It would be a devastating loss at this point added to an already tattered and barely surviving soul.

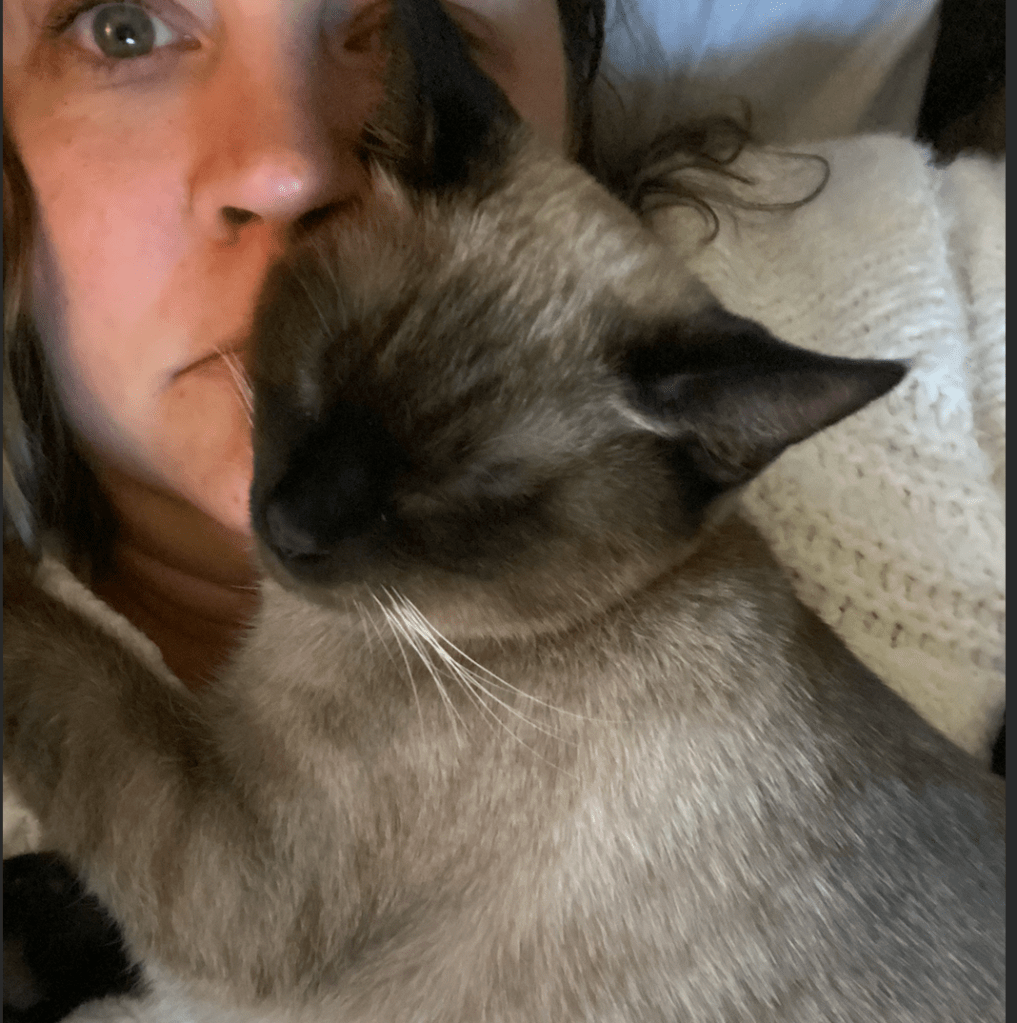

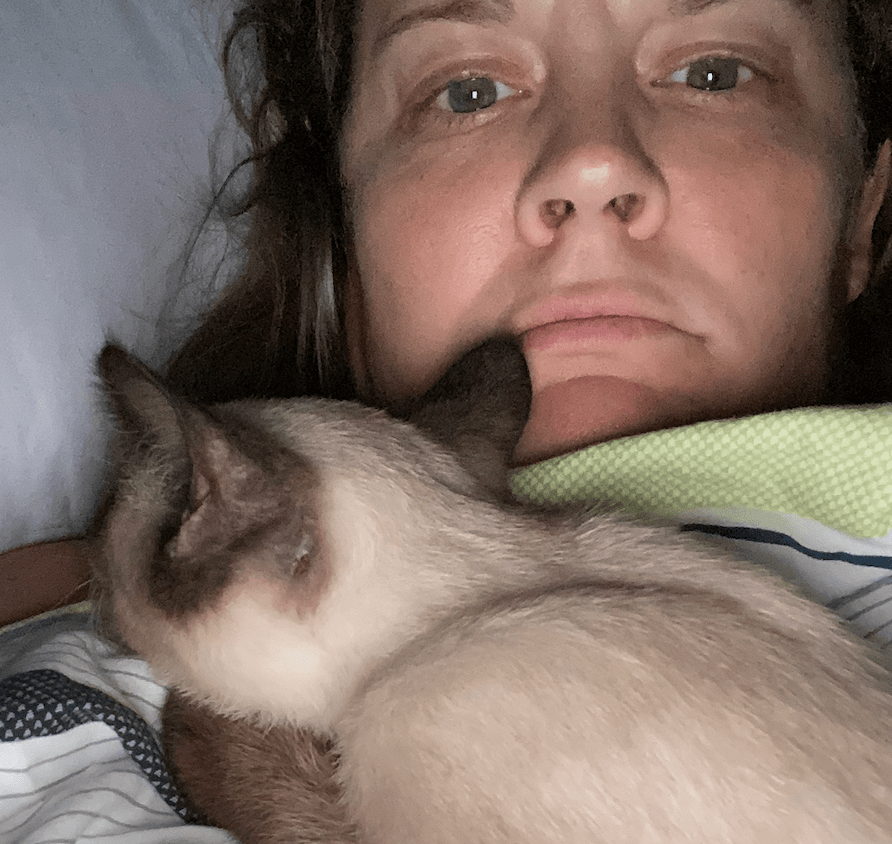

Because in truth, the past week had been a mix of healing vibes and guilt filled grief. Each night I went to sleep in the master and T in the guest room. That way neither Stella or Rooney were alone. I spent the first week falling asleep with my hand in Stu’s spot and Stella curled up on my chest, tucked under my chin. I didn’t sleep much. I’m a side sleeper and she was too damn cute to move. It was like she knew what was broken inside of me and she laid there, on my heart, not for her comfort, but for mine.

When the vet finally saw her, it was Dr. Plott again, he confirmed what we’d already suspected: Stella was in perfect health.

No fleas. No mites. Some worms.

Clear eyes. Good weight.

Friendly enough, considering.

She also wasn’t microchipped (she is now).

Thank God for small favors.

At least there was no proof of our crime.

I might have panicked for a moment when Dr. Plott asked, “where did you get her? You don’t see many Siamese strays.” But I managed to stammer out some “oh you know, a friend found her wandering about” response.

I brought her home, relieved, triumphant, and yes, still guilty and broken.

Yet, every night, I would crawl into bed with this stranger, this new kitten, and that was essential.

Not because I knew her.

Not because she’d earned it.

But because something had to fill the hollow.

Because the silence was too loud.

Because she curled into the space where Stuart used to sleep and didn’t flinch when I cried.

She was soft, and small, and steady.

And even if she wasn’t him, she was here.

And that was something.

This became my routine for about nine months. We were still in the pandemic and I was still working from home. She slept with me at night, sat on my shoulder while I worked or chewed on my papers. She snuggled up with me on the couch when she wasn’t sitting on Rooney or tormenting her as we made and ate dinner and let the day wind down.

I started to heal. I cried less and less. Sometimes I actually put on Stu’s Jams or scrolled through my pictures because I was afraid I was losing him, I was afraid I was letting go, and despite what grace she had given me, I wasn’t ready for her to take his place.

In the end, Stella made that decision for me. I went back to work and T started working from home. She went from snuggling with me to lounging on him during our evenings, and sleeping exclusively with him. She pulled away first. It was like she knew she had done her job, her services were rendered, and she didn’t owe me anything else. Now she was free to make her own decisions and play by her own rules. To this day she loves him more. I’m ok with that, even though I complain about it often and openly. She sasses me when I pick her up, I swear her meow sounds like “noooooo”. But every so often, she still comes into the bedroom, crawls up on my chest and lays on the heart she once helped me heal.